Published in the Sunday Navbharat Times on 26 January 2025

And this is how you apply ittar. Fukran explained to us in the most melodious voice, as he took a small dab of the perfume, rubbed it into his hands, and then gently applied it on his shirt—first over the chest, then the shoulders, and finally the arms. “Ittar is more concentrated than perfumes,” he said with a shy smile, “and it has to be applied on the dress, not the skin.” As he spoke, his words carried a magical rhythm, blending Hindi, Arabic, and Urdu in a manner so sweet and poetic, it felt as if they were dripping with honey. I could sit there and listen to him forever.

I fell in love with a particular ittar called “Mitti”. The moment I opened the bottle, I was transported to the end of summer and the start of the monsoon. It was as if the essence of parched earth welcoming its first raindrops had been miraculously bottled up in that tiny vial. Fukran stopped midway, refusing to continue unless we sat inside his little shop. As his guests, he wouldn’t allow us to stand while he showcased his perfumes. I finally understood the famous Lucknowi tehzeeb- culture and grace that I had heard so much about.

The word “Tehzeeb”, loosely translated from Arabic, means etiquette or manners. But in Lucknow, it encompasses so much more. Tehzeeb is a way of life—it is reflected in one’s speech, literature, recreation, dress, worldview, art, architecture, and, of course, the rich cuisine of this city.

Lucknow had been on my travel wishlist for years, yet somehow, I’d never managed to visit. A few months ago, a food tour idea with friends became the perfect excuse to turn this long-standing dream into reality. And they say the way to Lucknow is through its belly—but this city had much more to offer than just its famous food.The centerpiece of Lucknow is undoubtedly the trio of architectural marvels: Bara Imambara, Chota Imambara, and Rumi Darwaza—now, incidentally, a favorite spot for pre-wedding photoshoots as we witnessed on our trip there. Known as the land of the Nawabs, Lucknow’s identity is deeply rooted in the legacy of these rulers. The title "Nawab" has its origins in the Persian phrase “Naib” or “Nun-Wab”, which means "bread provider" or "caretaker of sustenance." This reflects the Nawabs’ responsibility as governors to provide for and protect their people. Over time, the title evolved into one of princely grandeur, symbolizing power, sophistication, and cultural patronage, and became synonymous with

The Bara Imambara and the Rumi Darwaza were constructed as a famine relief measure in 1784 under Nawab Asaf-ud-Daula. Designed by architect Kifayatullah, the 164-feet-long and 52-feet-wide Bara Imambara is constructed entirely of brick and high-quality limestone. Its arched roof is a true marvel, being the largest of its kind in the world, built without a single beam. Over 200 years later, the structure still stands tall, maintaining its original dignity and grandeur. One of the most fascinating aspects of the Bara Imambara is its Bhulbhulaiya, a labyrinth of narrow passages, intricate balconies, and 489 identical doorways designed to make visitors feel completely lost. The Imambaras are places of sanctity and worship, and unfortunately, they recently made headlines for the wrong reasons. After a social media influencer filmed a dance video here, the authorities decided to ban video recordings in the premises to preserve the dignity of the space. It made me reflect on our responsibility as tourists to maintain the sanctity, respect, and cleanliness of the places we visit.

We also stopped by the Chattar Manzil, the “Umbrella Palace,” which was once a beautiful residence of the Nawabs. Though now lying in ruins, it still carries echoes of its grandeur, although in a fragile state and we tread there as carefully as we could while exploring it.

Lucknow’s cuisine is legendary, and it lived up to every bit of its reputation. From kebabs and biryani we also. Had a chance to relish the winter delights like kali gajar ka halwa and makhan malai also known as Malaiyo in other places in North India, the variety and richness of flavors were unparalleled. Non-vegetarian dishes stole the show, but there were plenty of vegetarian options for everyone to enjoy. We sampled the famous chaat, bursting with tangy and spicy flavors, and indulged in meals prepared with age-old recipes that felt like culinary masterpieces.

One highlight was the home-cooked food experience at Naimat Khana, where the simple yet flavorful dishes left us speechless. On the last day, we indulged ourselves at the luxurious Saraca Hotel, dining at Azrak, where we savored the 12-hour slow-cooked Raan.

Of course, the best discoveries were hidden in the city’s bylanes—small, nondescript eateries that looked intimidating at first glance but delivered some of the most incredible food I’ve ever had. With a local guide, we unearthed these hidden gems and heard the fascinating stories of their origins, many dating back generations.

And then there were the famous Tunday Galawati Kebabs—a dish with as rich a history as its flavor. Legend has it that these melt-in-your-mouth kebabs were created for an aging Nawab who had lost his teeth but still craved the taste of kebabs. This inventive recipe, passed down through time, continues to delight food lovers across the world.

Not everything was a hit, though. The “Dabangg Tea,” popularized after the movie Dabangg was shot here, wasn’t my favorite—it was too creamy for my liking. I skipped the Kashmiri tea and stuck to the galawati kebabs instead!

We couldn’t leave Lucknow without its most iconic souvenir—chikankari embroidery. What was meant to be a quick shopping stop turned into a two-hour spree, with suitcases overflowing with intricately embroidered dresses. From wholesale markets to boutique designer stores, Lucknow offered endless options.

The motifs in chikankari are often a reflection of Lucknow’s architecture, including the fish symbol—a recurring motif in Nawabi art and culture. In Persian and Islamic traditions, the fish (mahi) symbolizes luck, fertility, and abundance. The Nawabs of Awadh, who were of Persian descent, adopted this as a central symbol of their governance and aesthetics.

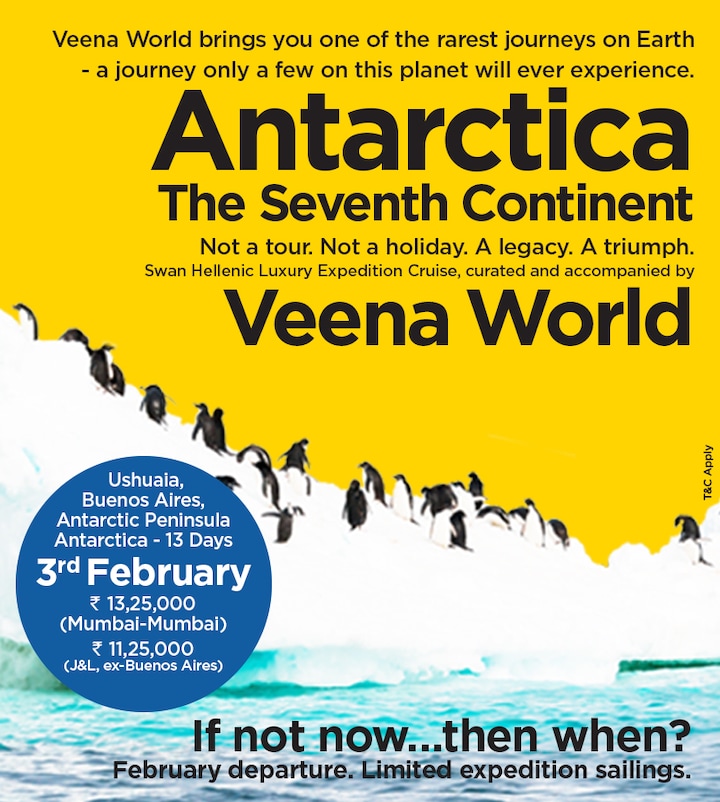

The fish can be found on gateways, royal banners, and facades of historical structures, often as part of the Mahi-Maratib, an order of honor and rank awarded by the Nawabs to military commanders and officials. Representing prosperity and protection, the motif is woven into the cultural and artistic identity of Lucknow. If you cannot wait to visit Lucknow join veena Worlds tour of Lucknow, Ayodhya and Varanasi, a beautiful blend of cultures that is the essence of India.

As I wrapped up my journey, I couldn’t help but marvel at Lucknow’s unique charm. Its air hummed with history, and its people exuded warmth, speaking in the kind of poetic, refined language that influenced even us. By the end of the trip, we found ourselves speaking chaste Hindi, promising to carry the tehzeeb of Lucknow back home with us.From its opulent history to its heartwarming people, every moment feels like stepping into a beautifully scripted story. Whether it’s the whiff of ittar, the taste of kebabs, or the echo of history in its grand architecture, Lucknow lingers long after you’ve left.

Post your Comment

Please let us know your thoughts on this story by leaving a comment.